Republic of Congo President Denis Sassou Nguesso and Russian President Vladimir Putin. (Photo: kremlin.ru)

To gain insight into Russia’s governance model in Africa, one only need look at the experience of the Central African Republic. Russian mercenaries with the notorious Wagner Group, ostensibly brought into CAR in 2018 to help stabilize the beleaguered government of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, now control diamond and gold mines in the north of the country and have warned UN peacekeepers to steer clear of Russia’s area of control.

“Wagner is, in fact, an off-shoot of Russia’s GRU intelligence agency.”

While commonly referred to as private military contractors, Wagner is, in fact, an off-shoot of Russia’s GRU intelligence agency. The private contractor designation provides Moscow a degree of deniability over the actions of the paramilitary group, which include charges of extrajudicial killings, rapes, torture, and arbitrary detentions. Wagner’s deployment of an estimated 2,300 “instructors” has provided Moscow leverage in a context where it has historically had little presence.

Gaining leverage by swooping in to provide an isolated leader security support follows the script Russia has used in Syria, eastern Ukraine, and Libya, among other places. In CAR, this move was matched by the appointment of a Russian, Valery Zakharov, as CAR’s national security advisor. Wagner troops also serve as the presidential guard. Touadéra’s symbolic and actual dependence on Russia couldn’t be more evident. CAR politicians who have protested the outsized Russian influence, including the former foreign minister, Charles-Armel Doubane, have been sacked. Three Russian investigative journalists attempting to gain more details of Wagner activities in CAR were assassinated in 2018.

Having negotiated a waiver to the UN arms embargo in CAR, the Russians were able to import weapons that are now seen as part of an arms-for-resources deal. The region is strategically located on a trafficking corridor linking western Sudan and eastern Chad through CAR and to the coast and transnational criminal networks. Sometimes seen as a hapless pawn of the Russians, Touadéra is allegedly a full partner in the trafficking scheme. Meanwhile, ordinary citizens face ongoing insecurity, poverty, and instability.

Presidents Faustin Archange Touadera of the Central African Republic and Vladimir Putin of Russia. (Photo: kremlin.ru)

Little wonder that the Russians were actively involved in Touadéra’s reelection in December 2020, maintaining a heavy thumb on the scale of the entire electoral process. The Russians lavishly funded Touadéra’s campaign, sponsored information campaigns touting Touadéra’s successes (and Russia’s positive role), and intimidated political opponents. The electoral commission and vote tallying process were closely controlled by Touadéra allies generating an unsurprising first-round victory.

The upshot is that in just a few years, Russia has effectively compromised the sovereignty of an African state. Given Russia’s financial and political benefits under this arrangement, dislodging them will be no easy task for CAR citizens.

While Russia’s brazen cooption of Touadéra in CAR may be the most well-documented case, it is just one of roughly a dozen places where Russia is, to varying degrees, reshaping the African governance environment—to the detriment of African sovereignty and democratic development.

Motivations

While Russia’s engagement in Africa is frequently characterized as opportunistic, Moscow has clear governance objectives guiding its actions. Vladimir Putin has said the liberal international order has become obsolete and has advocated for a multipolar world where democracy is but one of several viable governance systems. Putin’s post-liberal international order envisages more limited space for an active civil society and human rights protections. It entails moving away from a rules-based international system to one defined by transactional relationships between leaders. As such, Putin’s vision is less a new international order as a return to a 19th-century laissez-faire model unencumbered by international standards for political or human rights.

“Putin’s vision is … a return to a 19th-century laissez-faire model unencumbered by international standards for political or human rights.”

Driving Putin’s world view is a fear of popular “coloured revolutions” sweeping away long-entrenched authoritarian governments, including popular movements for democracy that have taken hold in neighbouring Ukraine and Belarus. Putin aims to blunt any momentum that could catch fire in Moscow. Advocating for an alternative to a liberal international order, therefore, is self-serving. It attempts to validate forms of governance other than democracy as equally desirable and legitimate. To the extent this is accepted, it reduces scrutiny and pressure on Russia itself to democratize.

Debasing the liberal international order also levels the playing field for non-democratic actors like Russia, which can better compete for influence in an arena where upholding norms of human rights, transparency, and adherence to the rule of law are optional.

Strategies

Russia’s attempt to influence Africa’s governance environment takes various forms. All revolve around some type of elite-level cooption. Paradoxically, elite cooption is used as an asymmetric tool by Moscow, well-matched to the relatively modest resources Russia brings to its Africa engagements. It doesn’t demand long term investments and relationship-building across multiple sectors of shared interests, as do traditional bilateral relations. It certainly doesn’t involve broad-based popular engagement. Rather, it simply requires the capacity to influence pliable individual leaders at the top of a hierarchical power structure.

The most common form of cooption involves a combination of Wagner or political support to beleaguered African leaders with access to natural resources. In addition to Touadéra in CAR, Russia has used this approach to enhance its influence with Denis Sassou-Nguesso in the Republic of Congo, Ali Bongo in Gabon, Filipe Nyusi in Mozambique, Andry Rajoelina in Madagascar, Emmerson Mnangagwa in Zimbabwe, Salva Kiir in South Sudan, and Alpha Condé in Guinea, among others.

Russia will at times simply back a non-democratic alternative. In Libya, Russia has been trying to implant Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar as a new strongman to give Moscow unprecedented access in the eastern Mediterranean. The coup led by Colonel Assimi Goita that displaced Mali’s democratically elected government in August 2020 was allegedly planned in Russia as members of the Malian military participated in extended training. A deal to send Wagner troops to Mali is now under discussion. In Sudan, Russia has reportedly urged military leaders to resist the planned transition to civilian rule. To the extent these proxies gain traction, they are not only indebted to Moscow for their rise, but they effectively supplant democratic norms for attaining power on the continent.

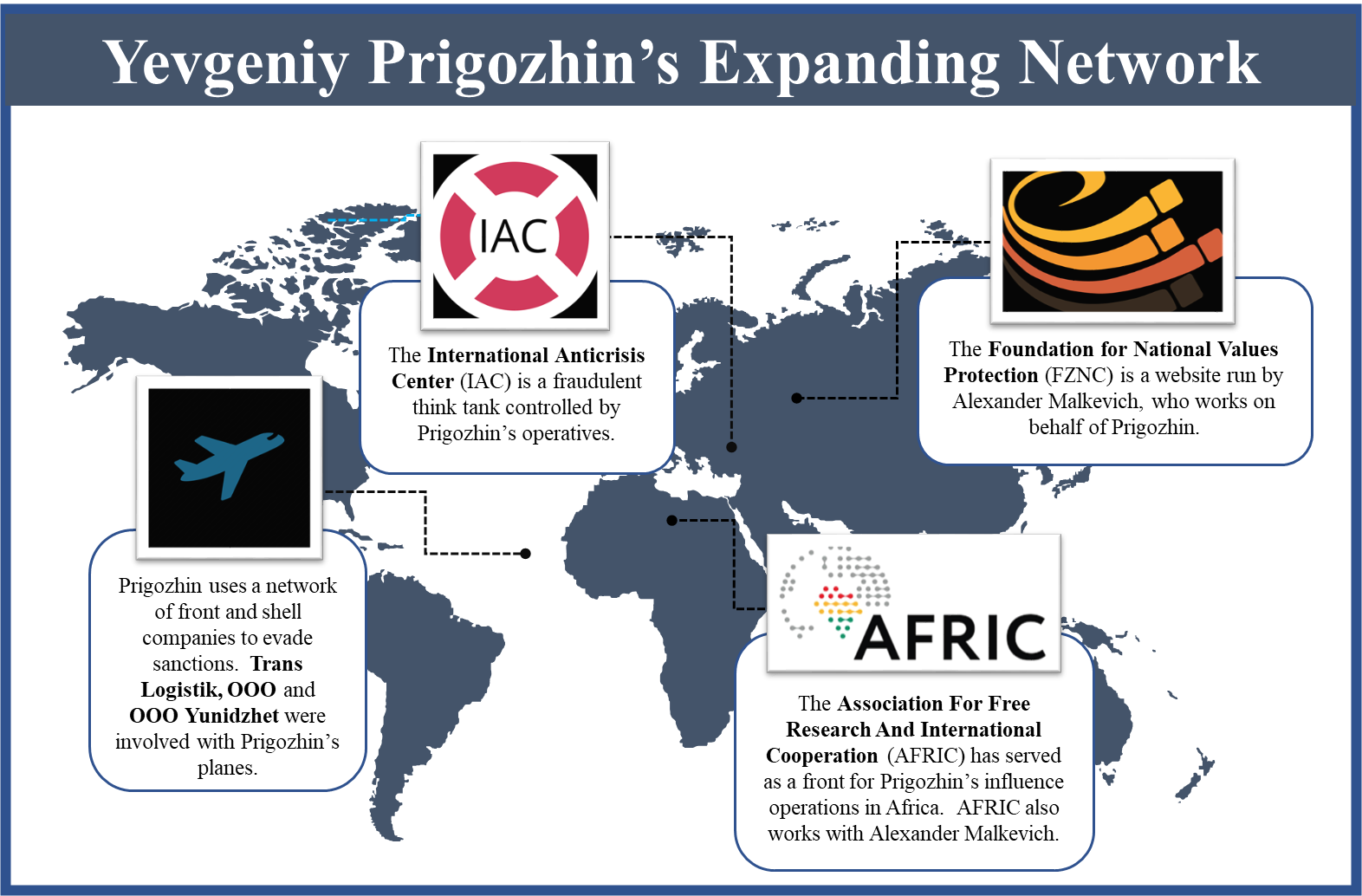

(Image: Treasury.gov)

As in other parts of the world, Russia is also active in election meddling in Africa. This typically involves surreptitious messaging supportive of a preferred candidate coupled with unfavourable representations of opposition candidates, dissemination of flattering, if dubious, polling figures to the media, and the unqualified and timely endorsement of election results by a pseudo-election monitoring organization, such as the Association for Free Research and International Cooperation (AFRIC). Such methods were on display in recent elections in Madagascar, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe, among others.

Disinformation has been another mainstay of Russian engagement in Africa—and efforts to undermine democratic processes. In addition to the campaigns supporting specific candidates, Russia has mounted a broader messaging effort disparaging democracy. The themes of this messaging revolve around democracy’s ineffectiveness and weakness, the futility of supporting any candidate, and the inherent trade-off between democracy and security—essentially an advertisement for strongman rule. By suggesting there are no real differences between political systems (and therefore no real advantages of democracy), the messaging encourages a passive fatalism among citizens to simply accept their elite patronage-based governments as no worse than the alternative.

In cases where Russia already has a privileged relationship with the incumbent, Moscow has a strong incentive to perpetuate their client’s time in power. This apparently is what the Russians had in mind in supporting Alpha Condé’s bid for a constitutionally prohibited third term in Guinea in 2020. When Condé faced widespread domestic opposition to his tenure extension, Russian Ambassador Alexander Bregadze attempted to provide cover by saying that “constitutions are no dogma, Bible, or Koran… it’s constitutions that must adapt to reality, not reality that adapts to constitutions.” Guinea happens to hold the world’s largest reserves of bauxite. Bregadze now heads up operations in Guinea for Rusal, Russia’s biggest aluminium company. Condé’s ouster from office following a coup in September 2021 is a setback to Russia’s cooption efforts. Yet, Moscow can be expected to simultaneously seek his reinstatement while attempting to duplicate the relationship with the junta leadership.

Vladimir Putin with Jacob Zuma of South Africa. (Photo: kremlin.ru)

The departure of South Africa’s Jacob Zuma was a major blow for Moscow. During Zuma’s tenure, Russia negotiated a $76 billion deal for a nuclear power plant. The deal was widely viewed as a boondoggle for graft to enrich Russians and Zuma’s allies, consistent with the larger pattern of state capture under Zuma. When Cyril Ramaphosa came into office, nixing this deal was one of his first priorities, saving South Africans from mountains of debt.

South African politics continue to be characterized by a battle between reformers and Zuma loyalists within the ruling African National Congress (ANC). According to forthcoming research by Dzvinka Kachur, in a bid to promote its nuclear power ambitions, Russia is allegedly contributing to disinformation messaging inflaming tensions and attempting to influence internal South African politics. Tensions between the ANC factions came to a head in July 2021 when Zuma was arrested for failing to appear in court on corruption charges stemming from his time in office setting off massive riots that rocked the country for days and incurred billions of dollars in damages.

Russia is apparently using the prospect of investments in nuclear power technology as another form of elite capture. In Egypt, Russia’s State Atomic Energy Corporation, Rosatom, provided a $25 billion loan to the Sisi government to begin work on a $60 billion nuclear facility. Like the arrangement with Zuma, this massive deal is widely seen as a hook for patronage at taxpayers’ expense. Rosatom has signed further preliminary nuclear power project deals with Ethiopia, Nigeria, Rwanda, and Zambia, among others.

Russia has also enabled Africa’s autocracies by supplying surveillance technology to monitor political rivals and civil society groups. Uganda and Rwanda have been notable clients of these tools.

There is an irony in Russia’s efforts to influence the governance environment in Africa. Russia uses the hallmarks of democracy—elections, open information platforms, and media—to orchestrate outcomes that advance Russian interests while sowing dissension and disillusionment among citizens in democracy itself. The veneer of democratic legitimacy bestowed on an African leader who gains or retains power through elections, even if under dubious means, is powerful. In the case of Russian-backed leaders, it also serves as a shield from criticism. After all, why should the international community complain about Russian mercenaries if they were invited by an elected leader? This scenario provides Russia the best of both worlds. It can manipulate electoral outcomes to its liking while basking in the glow of supporting a democratically elected leader.

Impacts

Russia’s governance engagements in Africa, like most external actors, mirrors its domestic political norms. Russia’s case entails an oligarchic, opaque, and patronage-laded system with limited means for popular participation or accountability. As this system is projected onto Africa, it cultivates a notion of African agency as the prerogative of individual leaders. This dovetails with Moscow’s elite-focused cooption strategy, providing Russia with outsized influence despite relatively marginal private sector, infrastructural, or development investment.

“Russia’s elite influence strategy negates citizen-based agency.”

Most relevantly for democracy in Africa, Russia’s elite influence strategy negates citizen-based agency. Polls show the vast majority of Africans prefer democracy as a system of governance and want to see stronger democracies take root on the continent. This is supported by a growing trend across Africa of popular protests demanding more participation, transparency, and accountability of their political leaders.

The competing visions of African agency overlap with the continent’s stark demographic divide. Africa is the world’s youngest region, with a median age of less than 20 years old. These youths are often at the forefront of calls for reform and greater levels of democracy (e.g., #EndSARS, Sudan, Algeria, Uganda, Togo, Guinea, Senegal, and Eswatini).

Resisting these calls for change, often, are entrenched African leaders who are clinging to robust executive authority with weak institutional checks and balances. A full quarter of Africa’s leaders have been in power for more than 20 years. Nearly all hold some form of elections, providing the façade of democracy. However, less than ten out of 54 African countries allow genuinely fair political competition, popular participation, and protection of civil liberties and political rights. In recent years, a trend of disregarding term limits has further extended tenures in office. This inability to shake off the legacy of strongman rule goes a long way toward explaining Africa’s stunted democratic development over the past decade.

It is into this reform vs. retrench split-screen view of Africa’s governance future that Russia is plying its influence, fully weighing in on the side of the old guard. From this perspective, it is evident that Africa’s personality-dominant, patronage-based, and institutionally weak political structures are ripe for Russia’s elite-based cooption strategy. The strategy is effective because there is active complicity on the part of African leaders who are selling out the interests of their compatriots to forge client-patron relationships with their Russian interlocutors. The big losers from these elite deals are ordinary citizens—and persistently diminished democracy.

Priorities

Africa represents a permissive environment for Russia’s influence and counter-democracy campaign in Africa. Changing this pattern—and the negating of democratic aspirations in Africa—will necessitate drawing attention to and, ultimately, weakening these elite actor cooption pacts. Doing so will require increasing the costs to both the Russian and African partners in these exclusionary alliances. Many of the needed actions can be framed as strengthening the sovereignty of African citizens vis-à-vis elites.

Vladimir Putin with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. (Photo: GovernmentZA)

Raising the profile of opaque collusion between African leaders and their Russian counterparts, and how each side benefits, would serve the purpose of educating the public and increasing transparency. African leaders who are undermining democratic processes would, in turn, bear greater reputational costs for their actions.

To be clear, the aim is not to vilify all ties between Russian and African diplomats. However, arrangements where African leaders are propped up via mercenaries, arms for resource deals, opaque contracts, and disinformation campaigns merit greater notoriety for all sides involved.

The African Convention for the Elimination of Mercenarism was ratified in Libreville in 1977 and entered into effect in 1985. This convention prohibits states from allowing mercenaries entry into or safe passage through their territories. It similarly forbids the recruitment, training, and financing of mercenaries or any activities likely to promote mercenarism. As a means of regaining African sovereignty and the exploitation of weak states through the deployment of mercenaries, the African Union should reexamine its application of the Libreville Convention and hold states accountable for upholding its provisions.

The African Union and civil society activists can also make a renewed push to require that all natural resource and public service contracts be made public as a means of ascertaining how the allocation of these public funds benefits citizens. Currently, 29 African countries are members of the Publish What You Pay alliance. They must do more to hold one another accountable to these standards. Similarly, reformers can also push to make all such contracts subject to legislative approval before they can be finalized as a means of enhancing transparency and accountability. Notably, 22 of 28 resource-rich African countries have recently amended laws governing the oil, gas, and mining sector to make these more transparent. Much room for improvement remains in implementation and enforcement, however.

The very nature of disinformation is opaque and intended to conceal the source of the misleading or polarizing messaging. Uncovering this often takes concerted effort and expertise by watchdog groups. Accordingly, only a fraction of disinformation is exposed. Expanding the number and capacity of these watchdog groups in Africa is a way to expose more of this disinformation quickly.

“Russia has made headway in reshaping governance norms in Africa in line with Vladimir Putin’s vision of a post-liberal international world order. Russia has thus far faced minimal costs for these actions.”

Election meddling is a grave violation of another country’s sovereignty. Effectively, it is a brazen attempt to control whom a sovereign nation elects as its leaders. These violations, therefore, must face far stiffer penalties than have been the case. In addition to criminal charges against violators, severe sanctions should be imposed on state actors who may be involved. This should be reinforced by penalties against financial institutions involved in sponsoring the meddling. This would force these financial institutions to elevate the scrutiny and due diligence for support to groups with a history of election interference.

International democratic actors should also invoke their equivalent of the Global and European Magnitsky Acts, the Global Fragility Act, and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act to impose sanctions on individuals, institutions, and governments found to be responsible for undermining democracy and stability in targeted African countries.

International democratic actors can furthermore strengthen democracy in Africa by incentivizing democratic governance. Among other things, this will reward the legitimacy of democratic government via heightened diplomatic recognition, financial support, and bilateral cooperation. Affording all African governments equivalent levels of diplomatic recognition, regardless of the way they’ve come to or maintain power, encourages democratic minimalism, that is upholding the merest pretence of democratic processes. This is especially the case when a key source of support for these leaders is a foreign autocratic power.

Recognizing the divergence in elite vs popular agency underscores the need for greater support for citizen movements advocating for greater democracy. Citizen protests for electoral transparency, against third termism, and in defence of human rights and civil liberties deserve the support of international democratic actors. These global leaders need to act decisively if such displays of public expression are suppressed. Fraudulent elections should be called out, audits demanded, and reruns organized, when warranted, to ensure the voice of ordinary citizens is not muffled by elite bargains.

Russia has gained considerable influence in Africa in recent years through its strategy of elite capture. This has contributed to democratic deterioration and the thwarting of the aspirations of hundreds of millions of African citizens. In the process, Russia has made headway in reshaping governance norms in Africa in line with Vladimir Putin’s vision of a post-liberal international world order. Russia has thus far faced minimal costs for these actions, which compromise African sovereignty. Until democratically committed African citizens, governments, and international partners can organize tangible diplomatic and financial costs on these egregious actions, Russian efforts to co-opt African leaders can be expected to continue.

This article first appeared on democracyinafrica.org as part of a Special Issue on “Authoritarian Regimes in Africa.”

More on: Democratization Disinformation Russia